|

The content of this CD is a collection of audio

files extracted from the first part of a very wide in

scope multimedia project, (commissioned by HOMO

ECUMENICUS Publishing), which explores the whole range of

ancient Greek music, but also of Greek culture in

general, because, in my view, the music of ancient Greeks

can not be studied separately from their literature,

poetry, drama, religion, and even their social and

political life. This first part deals with the early epic

and lyrical poetry and covers the period between the 8th

and 5th centuries B.C. The other parts' subjects are: the

Homeric Epics, the Orphic Hymns, the Dramatic Poetry (Aeschylous,

Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes), and the

music of the Hellenistic and Roman period.

Creating this project has been a great challenge for me

in many respects: As a musician, to compose and perform a

kind of music completely different from the mainstream,

the fruit of a long-time exploration in the roots of the

musical art, especially as this has been expressed in the

Mediterranean, the Middle East, the Balkans and Western

Europe. As an MA in Digital Media, by taking advantage of

the creative capabilities of the new media, to attempt to

reconstruct the musical experience of ancient Greeks not

only as sounds but also as texts, images, video and

interactive features. Finally, as a researcher in the

field of antique Greek culture and philosophy, to show

the timeless and classical value of this culture and to

argue that it is not a dead thing of the past but the

living heart of human civilization, evident in the

world's languages, in our thinking, in the organization

of our societies, and in every aspect of artistic

expression. The study of ancient Greek music in

particular (lyrics, metrics, modes, notation etc.) gives

sufficient evidence that this music lies in the

foundation of both the western and the eastern musical

tradition. The manner in which Western culture in

particular has expressed itself in the art of music has

been profoundly affected by Greek musical thought and

practice.

It is well known that the early

Christian church modes drew upon the ancient Greek modes.

First the Gnostics used the Greek scale in their

incantations, and then Byzantium not only adopted the

Greek modes but also adapted the verses of ancient poetry

to praise the God of the new religion. In the hymns of

today's Greek Orthodox Church which saved unaltered the

Byzantine tradition of the early Christian church, the

relationship with the ancient Orphic hymns, as well as

with the whole range of Greek poetry, both Lyrical and

Dramatic, is obvious. Also, the huge legacy of ancient

Greek writings on music theory served as models for later

theoretical treatises and helped shaped the course of

Western and, of course, Middle Eastern music theory.

There is no aspect of the musical art that the ancient

authors did not deal with: Writings on theory, musical

education and the role of music in society (by Plato and

Aristotle), on practical aspects of music performance

(Aristoxenus), on acoustics (Pythagoras, Euclid,

Ptolemeos) etc. Even the notational system, on which

today's Western music theory is based, comes from the

philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras (6th century

B.C.) who was the first to define musical intervals in

mathematical terms and thus create the first system of

musical notation. Finally, the organized system of

Western harmony, as expressed in the so called classical

music is actually the evolution of the music of the

Middle Ages, the organization of which, in turn, derives

from the medieval theorists' knowledge of ancient Greek

music transmitted to Europe by means of the works of

Boethius in the 5th century A.D and the writings of Arabs

later.

However, despite its immense

contribution to the world's musical culture, very little

is known about how the original Greek music actually

sounded. Surviving songs are for the most part fragments

that have been preserved either as quotations in the

works of biographers, metricians, and grammarians, or as

passages on papyrus strips, that had been used to wrap

mummies and stuff sacred animals in the Hellenistic

Egypt. Some notated fragments that have survived, written

in a relatively late Greek notational system, do not

provide adequate information for a safe reconstruction.

Also, some relics of ancient instruments that have

survived, are not playable, so our understanding of how

the music sounded rests solely on speculating on how the

particular constructions could work in terms of

acoustics.

Research in this particular field

becomes even more problematic from the fact that most

researchers come from disciplines other than music (they

are either archeologists or classicists) and also the

majority of them are non-Greek natives and, as a result,

not familiar with the language, or with the contemporary

Greek music, which is the natural child of the ancient

one. In my view, if they had a background in music and

also were familiar with the ancient language, they would

recognize the intrinsic rhythms and melodies of the

ancient verses, almost untouched by time, not only in

contemporary Greek traditional music but in the whole

range of humanity's musical endeavors. They could see,

for example, the ancient hymns, paeans, encomia, hymeneoi, partheneia, elegies, dithyrambs etc. in the

love songs, religious songs, dance songs, drinking songs,

laments etc. of contemporary Greek, Middle Eastern,

Balkan and European folk music. If they tried to play the

ancient Phrygian or Hypodorian modes using any stringed

instrument, they would be surprised by how western these

modes would sound, and they would see the close

connection of the ancient rhapsodists and aoidoi with the

medieval bards and troubadours, and even with today's

singer-songwriters. If they were familiar with the

ancient Greek culture, attempts to reconstruct the music

would not result in monotonous recitations, based on

stereotyped assumptions that Greek music consisted

entirely of melodies sung in unison, and that there was

no polyphony or complex arrangements. In my view, this

music, being the product of a highly sophisticated

culture, which encouraged free thinking and creativity and

thus created masterpieces in all fields of artistic

expression, could not be an exception.

On this principle I based my own

compositional approach, without however breaking the limits imposed by

the current status of archaeological evidence. As notation for the songs

of this particular collection has not survived, with regard to melody, I tried

to accommodate melodic principles to the demands of the

verses by creating melodic movement from the natural rise

and fall of the text.

The modes I used were those that seemed

to me most appropriate for the lyrical subject, mood, or

occasion on which the particular songs were likely to

have been performed. I made use of all modes (except for

the Mixolydian mode), but in the majority of compositions

I used combinations of the most common modes: Dorian, Lydian, and Phrygian.

With regard to rhythm, I used the rhythm

of the words, as this was dictated by the accentual

structure of the Ancient Greek language, as well as by

metrical structures. Actually, the intrinsic rhythm of

the verses revealed to me the whole range of all known

rhythmical patterns including my favorite odd signatures

like 9/8 and 7/8.

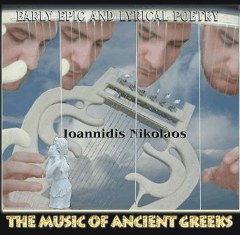

With regard to sound, in order to

emulate the ancient stringed instruments' sound, I used a copy of an

ancient kithara (the instrument featured on the CD cover), which I

patterned after surviving museum originals and iconographic

representations on sculptures and vase paintings. This instrument being a combination of a modern

classical guitar and a harp actually sounds both like a

guitar and a harp, and I believe that its sound can not

be very different of that of the original kithara. I also

used a modern classical guitar which I tuned like a

six-stringed barbitos or lyra, and which I played without

fretting. To emulate the sound of the ancient aulos (reedpipe), I used three woodwind instruments that

feature in the traditional music of Greece, Asia Minor

and the Middle East. They are the flogera, the zournas

and the ney. For percussion, I used the traditional Greek

instruments daires, defi and dumbek.

In my transcription of the Greek texts

I used all capital letters to avoid the problems associated with Greek fonts. Also, in order to make them more

readable I had to speculate on the missing pieces and

take the risk of introducing elements, for the sake of

lyric flow.

Finally, with regard to the translations

of the Greek texts which was not easy, due to the

fragmented nature of the material, I tried to make them

as literally as possible, while being faithful to the

original Greek text, that is by showing how phrase

follows phrase.

I believe that my approach, having been

based on the findings of a deep research and the

utilization of all available archeological evidence

cannot be very far from the actual music of ancient

Greeks. My hope is that this work will contribute a

little to the research in the field of antique Greek

culture, which in our turbulent times becomes once more

extremely relevant

Nikolaos Ioannidis

September 2002

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Editor's note:

The subject of the influence of Greek music on

the

musical cultures of the peoples,

who have been subject to classical Greek cultural influence,

has also been researched by the author in the framework of an academic research

project at the University of Sussex.

Information on this

research project is available at the URL:

http://homoecumenicus.com/ioannidis_doctoral_dissertation.htm

|